Distil

Distil

A compilation of my favourite copywriting work across clients at Distil.

Distil

QissaGoi

[Text on reels]

[Long-form captions]

[Long-form copy]

A compilation of my favourite copywriting work across clients at Distil.

[Text on reels]

[Long-form captions]

[Long-form copy]

An exploration of Instagram-focused visual poetry and storytelling.

My first attempt at creating a visual narrative around my videography was nearly unintentional. I had observed a pattern in the way I filmed, a kind of stillness that captured the thrumming movement of the world around me. The only thing left to say was a single word – ‘movement’. The little dance of everyday life.

I then hopped on a bit of an old trend, ‘humans’. The trend captured humans with our little quirks, habits, and rituals in fond observation. I once again noticed my own collection of the same over the years before I had even come across the trend. It felt apt to give it a shot from my eyes.

My work became more intentional here on. I began to actively seek out patterns and parallels in my immediate surroundings. On my daily walk to the bus stop, I noticed a hive of flies clinging to the weeds that grew out of the concrete. I immediately wondered, ‘what a strange acquaintance‘. The following week I came across a few more this way, some beautiful, and some ugly. I liked the way it brought the balance of the world in a simple statement, a friendship of the ugly and pretty.

My most recent piece was written before it was filmed. I had made note of this line in an essay for college on the topic of cultural linguistics. How I could see my grandmother’s hesitation with English in the way she phrased her sentences. How limiting that made her in expressing herself completely. I gratefully found this clip in my gallery recents soon after. A silent moment of love spoken between two people who didn’t particularly have language to share.

Short film adapted from Lihaaf, by Ismat Chugtai. The ideation and final product were a collaborative effort, in which I was selectively responsible for writing the script.

1. INT. DANCE STUDIO – DAYTIME

A group of Bharatnatyam dancers, with emphasis (close-up shots) on feet and hand movements, with transition/cut/dissolve to the shadow of their movements. The other dancers gradually leave, focusing on Kalki and her shadow movements.

Title card.

Kalki practises a choreography, rapid cuts with beats, her costume is traditional (Bharatnatyam attire – casual), and she has a stern, concentrated expression on her face. There is a small speaker in the corner of the room playing soft classical music.

2. INT. DANCE STUDIO – NEXT DAY

Kalki is practising again alone after her class. Repeat shots of choreography from the day before, only change costume, hair, etc. Alka enters the room with an assistant (Kathak attire – casual), pauses after seeing Kalki still in the room. Kalki is too involved in her performance to notice for a few seconds. Alka carefully watches Kalki for those seconds. The ghungru sound from Alka diverts Kalki’s attention, which makes her stop dancing. Kalki glances at the time and realises she has overshot her time there.

KALKI

I’m sorry, did you need the room?

Alka walks in without much of a reaction (maybe just offers an expression back). She begins to prepare for her practice (putting on ghungru, fixing hair, etc.). The assistant follows. A little frazzled, Kalki goes to switch off her music and begins to gather her things. The assistant goes to switch on the music. Alka positions herself in the centre of the room, begins stretching/warming up. The assistant follows, and they both warm up together. The assistant often assists Alka during. Kalki begins packing her things, zipping up her bag, etc. She hears the sound of Alka’s ghungrus. Her head turns in response, seeing Alka and the assistant dancing. There is visual emphasis on Alka’s grace and beauty as seen through Kalki’s eyes (brighter lighting, glow, and slow motion). The performance finishes. Alka approaches Kalki before she can leave.

ALKA

Come here.

Alka beckons Kalki, sits, and takes a sip of water. Kalki follows, stands awkwardly. The assistant sits beside Alka, she takes Alka’s foot into her lap, and takes off her ghungrus. She mindlessly begins to massage Alka’s feet.

ALKA

You may sit, beta. (gestures)

Kalki sits on her knees, attentive.

ALKA

I see I’ve caught your interest (she smiles). I’m Alka…your name?

KALKI (EMBARRASED)

Kalki, ma’am.

ALKA

How long have you been practising Bharatnatyam for?

KALKI

Around 5 years now.

ALKA

Under which guru’s tutelage do you practice?

KALKI

Guru Kunali. We have our practices from 2-3:30 every day.

ALKA

Ah, that’s why I caught you lurking around.

KALKI (EMBARRASED)

I never knew Kathak could be so… (looking for the word) evocative?

ALKA

Yes…you may not be familiar, I teach the Tawaif form of Kathak, are you aware?

KALKI

Not really, Alka ji.

ALKA

See, similar to how Bharatnatyam performers have origins as devadasis: temple dancers, the performers of Kathak were courtesans, known as tawaifs. But during the British Raj, some tawaifs began to practice mujra, which is more… erotic, or ‘evocative’ as you say (making fun).

Kalki laughs.

KALKI

Your performance… something about the bhaav, it felt different.

ALKA

If you trace back to Kathak’s Mughal origins, or its Sufi influence, the expression of love toward God transcends just devotion…which is what you will be familiar with in Bharatnatyam. Whereas here, the God and the lover are sometimes seen as one, we have the liberty to engage with the deity as their lover. What you may be observing is ada, which is exclusive to Kathak.

KALKI

How do I learn it?

ALKA (LAUGHS)

Well, that takes a great deal of time and dedicated precision to develop thehrav, and furthermore to achieve ada. These are ways in which we emote, or maintain elegance and control over our rhythm during performances. So that I can bring you, my audience, bhaav. Ada is not achieved in Bharatnatyam.

KALKI

Then…can I learn from you, Alka ji? I promise to be dedicated.

Alka smiles.

ALKA

I’ll see you at 4 tomorrow.

4. EXT. DANCE STUDIO – EVENING, NEXT DAY

ESTABLISHING SHOT/INSERT SHOT (SYMBOLIC METAPHOR)

Match cut using gungrus (Feet shot)

5. INT. DANCE STUDIO MONTAGE

The assistant and Alka are practising a choreography. Kalki sits in a corner of the room, watching. Kalki’s feet tap restlessly to the beats, she imitates their movements subtly.

6. INT. DANCE STUDIO – EVENING, NEXT DAY

Alka arrives without the assistant. Kalki, as before, retreats to her corner of the room. Alka begins her practice. At a point during her practice, Alka hesitates. She attempts a step a few times, but seems to be frustrated.

ALKA

Kalki, can you come here?

KALKI (SURPRISED)

Yes, sure, ma’am.

Kalki gathers herself, approaches Alka. Alka guides her closer.

ALKA

This piece is my first experimental ensemble work, not common in traditional Kathak practice. So I would need a partner for this part…for now, you’ll have to fill in. Did you follow?

Kalki nods eagerly. She had already somewhat grasped the steps, but her movements were rigid. Alka touches her waist to encourage more flow. Kalki jerks slightly at the touch.

KALKI (SOFLY)

Sorry…

Alka begins to adjust Kalki’s movements. Out of habit, Kalki bends her knees, spins on her toes and emotes expressively. Accordingly, Alka corrects her.

ALKA

See here? In Kathak, you don’t bend your knees this way.

Alka uses her knee to nudge the back of Kalki’s knee. She similarly nudges her foot to the back of Kalki’s foot so that she drops from her toes and uses her heels during spins. The shots are cut one after the other, each time Alka adjusts Kalki. Kalki is initially frustrated, but the shots repeat, showing her quickly catch up. Alka is ready to adjust her, but Kalki has already caught on. At one point, Alka ceases her own performance in order to watch Kalki. Kalki, engrossed and dedicated to completing the sequence, has almost perfected the piece. Yet, Alka’s expression shows discontent. Kalki’s performance ends.

ALKA

You’re almost there, but one thing is missing. I want to try something tomorrow. Come again, same time.

KALKI

Yes, Alka ji.

Kalki kneels all the way down to touch Alka’s feet (with her head) in a gesture of respect. Alka laughs and adjusts her once again, prompting her to stand upright and bend rather than bend all the way, showing her how it’s done in Kathak. Kalki leaves smiling/beaming.

7. INT. DANCE STUDIO – NEXT DAY, EVENING

Alka is in the middle of the room with Kalki, setting her bag down/getting ready. We see Alka trace the room, humming to herself as Kalki watches her. Kalki finishes getting ready and walks up to Alka who is now standing still (Alka asks Kalki to perform a specific narrative sequence: Gopi Vastraharana (‘theft of the gopi’s clothes’), which recounts Krishna’s playful theft of the clothes of the female cowherds, the gopi’s, who had left their clothes on the Yamuna River bank while bathing. Krishna places them high in the branches of a tree, in which he is seen perched, daring the gopis to venture from the water. Metaphorically, this story serves to convey the power of devotion, to stand vulnerable before one’s God, secure in the power of bhakti, the unquestioning devotion to one’s god.)

ALKA

Today, we will perform one of my favourite sequences. The Gopi Vastraharna. Are you familiar with it?

KALKI (SOFLY)

Yes Alka ji, a little…

ALKA (CUTTING HER OFF)

It is a tale that follows lord Krishna’s theft of the female cowherder’s , the gopi’s clothes.

Grabs her hands/shoulders from the back and begins circling her.

ALKA

I want you to embody the Gopis in this sequence. I want you to feel their vulnerability and devotion to lord Krishna.

Alka walks away to turn the music on as we focus on an intimidated Kalki.

ALKA (OS)

Remember! your bhaav must reflect the Gopis’ emotions as they stand exposed before Lord Krishna.

Kalki seems to have the hang of everything, except her bhaav; she is too naturally/habitually emotive. At one point during the performance of this narrative, Alka stops her.

ALKA (SUCKING HER TEETH)

Kalki, your expressions are too pronounced. In Kathak, ada (grace) requires subtlety and control. Let your body speak as much as your face.

(PAUSES)

Here, let me come help you, I will play the role of Krishna.

KALKI (SHEEPISLY)

Yes, Alka ji.

Alka offers to come on stage with Kalki to help Kalki better visualise the role of Krishna. She criticises Kalki for emoting too superficially, and that if she must master ada, she will be required to immerse herself more subtly, with better control of her emotional range and expression. Similarly, Alka encourages her to try and use her body/movements to emote instead. The shadow play begins here, intercutting the performance with shadows of it on the wall. The music, along with the performance, reaches a crescendo. Alka’s touch in the shadow shot is explicitly inappropriate. The chun chun of the ghunghru is especially loud. Kalki jerks in reaction; her movements are hindered, but she continues. The performance ends. This is in parallel to the part of The Gopi Vastraharana, where the gopis are expected to venture out of the water naked and vulnerable in devotion to their lord, Krishna. Kalki’s shame is evident after she has been touched, but in devotion to her guru, she completes her performance.

ALKA (STERNLY)

So? Did you finally understand?

KALKI (DISTURBED, AFTER THE TOUCH)

I… I understand, Alka ji

Kalki has her head held low, eyes wide like a deer in headlights. In her disturbed state, Kalki hastily gathers her things to leave. She bends in respect, about to touch Alka’s feet. Halfway almost entirely down, she remembers, and straightens her knees. She touches Alka’s feet and leaves.

KALKI

Thank you, Alka ji. I’ll be off.

Alka notices the disturbance, but remains quiet. The door closes behind Kalki.

INT. DANCE STUDIO – DAY

Kalki arrives at the studio during a time when no one is occupying it (outside class hours). She enters, sets her things aside and places her speaker at the corner of the room. She begins to prepare herself for a solo practice. While she is tying her ghunghurs, she gets frustrated by the knots in them. She makes a few attempts to untangle them, but in her irritation and distracted/troubled mental state, she ties them as is. On stage (at the centre of the studio), Kalki begins her practice. Once again, the performance is intercut with shots/flashbacks of Kalki’s previous session with Alka. Each time she was touched is now played back as disturbing or uncertain. The shadows appear on the wall in intervals, until she notices Alka’s shadow joining her. The shadow touches her, shocking Kalki out of her performance. Her ghunghru breaks. She turns back to see that there is no one behind her. Heavily breathing, Kalki has entirely snapped out of her performance. The shot lingers on her, and then fades to black.

INT. DANCE STUDIO – AFTERNOON

Establish time jump: 1 week later.

Back to the class of Bharatnatyam students. Similar shots to the opening sequence. The class is following a choreography. Focus is on Kalki as she follows the steps. She catches on quickly as always, but she hesitates when it comes to her spins, the way she bends her knees, and the lack of facial expression. Guru Kunali watches her from across the room. She makes a gesture with her hand toward her face to encourage Kalki to emote more. Finally, she walks toward Kalki and places her hand on her waist to adjust her posture. Kalki jerks at the touch. The ghungru sound is heard.

END.

The prompt given was an end-sem group short film adaptation of any short story of our choice, keeping in mind the learnings over a film adaptation course. My personal priority initially, was to use a simple yet effective source text which could both offer a space for creative adaptation and resemble the depth of the story adapted. My group mate, Sharif had recently watched our classmate Aditi, perform a Kathak piece for one of her assignments and was enamoured by the visual narrative it conveys. Sharif then proposed that we could use the form of dance in our adaptation, which I agreed was a great place to start. Sharif had also mentioned that he was keen to use the short story Lihaaf, by Ismat Chugtai.

Due to my, and my group’s unfamiliar background or knowledge of Indian classical dance, we decided to start by speaking to classmates, Maitreyi, and Aditi who come from Bharatnatyam and Kathak backgrounds respectively. Matreyi laid out the entire historic foundation of Bharatanatyam as per her knowledge which is where my group began to draw parallels to how we could adapt it with Lihaaf. I proposed that we could resemble the age hierarchy between the protagonist in Lihaaf and her aunt, Begum Jaan with a guru and shishya dynamic present in dance. Similarly, we ideated that the maid/helper from the source text could be an assistant or advanced student of the guru. Once we had ideated the roles we would resemble, we moved on to how we could capture key narrative elements and themes.

Sharif and I sat down and verbally ideated the progression of events that would take place, and how we would incorporate our little knowledge of dance to portray it. We deliberated how we could implement the complexity of female sexuality, age-based power dynamics, devotion and trauma, enabling the form of dance as a unique visual tool in the manner we could deal with it. We agreed the usage of shadow play from the source text was an impactful way to represent such themes, especially trauma, due to the uncanny discomfort and fear it instils in viewers. We were also interested in using aural symbols to further exemplify these themes, which is how we settled on using the sound of ghungroos. This is where we proposed the title Chhan Chhan, which would transition during the narrative from an amusing, pleasant sound to a more jarring and traumatic one. We composed the rough outline to the rest of our group, along with Aditi, who gave us insight into the role that Kathak could play in the story.

At this stage, we were satisfied with our progress and vision and met with our course Professor, Kunal Ray to propose the idea and gain any further inputs. He suggested how we could resemble our source text better, in terms of establishing a domestic space to offer an equation of proximity, the use of dialogue in enabling the narrative or in suggesting nuances of the themes, and how to develop the relationship between the guru and her assistant before introducing the student. Once we took note of the feedback, our group began preparing logistics and working on the script.

As I was the primary script writer for the film, I faced challenges grasping how to portray our idea in written text, especially considering our dependency on dance to convey the narrative. I spoke to a couple of other dancers that I had known, which greatly helped me visualise and implement detail in how we could approach the adaptation.

We took note of nuances which differentiate the form of Bharatnatyam and Kathak (the way they spin, bend their knees, pay respects to their guru, etc.), which I used to establish the growing relationship between Kalki and Alka. Further, my mother suggested I use the Gopi Vastraharan during the climax since the narrative sequence resembled our theme appropriately. Similar to how the gopi’s are expected to venture out of the water naked and vulnerable in devotion to their lord Krishna, Kalki expresses her devotion to Alka, by completing her performance even after there is evident shame and discomfort once she has been taken advantage of. There is a clear silence between the two, where Alka dismisses this discomfort, and Kalki is not in a position to express herself. The interplay of shadows in this scene was intended as a visual tool to reflect Kalki’s mental state and disturbance which is once again repeated when she reattempts the performance the next day alone. This establishes the intrusion of her trauma into the space of her passion for learning Kathak, opening questions of devotion, sexuality and trauma. I proposed the script to my team, after which Rohan helped me refine the dialogues.

Zahanya was primarily responsible for reaching out to actors and planning the shooting schedule with our available location, equipment and time requirements. Before shooting, we sat down with our actors to brief them of our plan, the script and which days we were aiming to shoot. At this stage, we gained more input on how to alter our dialogues (during the exposition of our story), such that they did not offend the form we were using, and said just enough to establish context for our film. We adjusted the script accordingly and began shooting.

Our single location was a campus dance studio which allowed us the freedom to shoot over a span of 3 days without too many continuity errors. Our only barrier was the mirrors in the room, which Sharif managed to skillfully leverage to work with our narrative. For example, the abundance of reflections of Kalki during her solo performance heightens the emotional intensity of her turmoil. He very carefully took over the shooting process, with the help of his friends who were familiar with using the equipment. Sharif then edited the film, which we were overall very satisfied with as a group.

The overall process gave me a great deal of insight into not only how to work with adaptation from a text to a visual medium, but also the tedious effort and collaboration it requires to accomplish. I was very passionate about the direction my group took and found the discovery of Indian classical dance as our channel, extremely rewarding.

A video essay on diasporic cinema: cultural negotiation of identity within the context of urban alienation using the film Persepolis and intergenerational discourse as my case study.

The beauty of cinema as a medium of representation is its ability to offer perspective and diverse expression of identity. Diasporic cinema is a genre of cultural negotiation regarding individuals in exile residing in a country away from their homeland. The medium taps into a selection of identity expression that deals with a complex conflict of cultural residue within the adaptation to a new environment.

Marjane Satrapi, is an acclaimed Iranian-born French graphic novelist, illustrator, and film director. Her internationally recognised graphic novel, Persepolis became an animated film adaptation in 2007. The film considers an autobiographical encounter of a young girl growing up within the backdrop of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Satrapi’s diasporic navigation through the complexities of coming of age in revolutionary Iran and later as an immigrant in Europe construct a tension between collective and individual identity. This case study approaches her narrative through a broader intergenerational discourse that supports the topic of identity negotiation, further intersecting into conversations on gender and cultural identity.

[Persepolis – Exclusive: Chiara Mastroianni]

The article, Out of the Family: Generations of Women in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis by Nancy K. Miller offers a redefinition of the notion of generation in terms of chronology. Her analogy states that generation can be understood in a parallel corporeal mental space through a collective coexistence of historic or cultural context. The realism of dialogue and memory, as recalled by Satrapi in her film, forms a collective intergenerational experience which transcends hierarchy in generation. Persepolis supports this coexistence of intergenerational identity through the lens of traumatic bonds and collective grief. The film uses its medium of animation to play with visual interludes to the narrative. After a democratic vote for the Islamic Republic, the three generations of the Satrapi family reveal a consequence of the change. Marjane’s innocent ignorance, her uncle Anoush’s reassurance, her grandmother’s distaste, her mother’s contemplation of escape, and finally her father’s reminder of their reality. With each generation, there comes a background of privilege, class and ideology in the way they face the consequences of the regime. And although Marji was granted freedom, it came at the cost of generational guilt, and conflict in cultural identity.

Marjane’s relationship with her grandmother is reflective of the tension she has with her cultural identity and the one she begins to curate to fit in abroad. The flower motif, for instance, is a recurring symbol throughout the film that toys with sensory recollection through visual repetition. The jasmine flower marks Marjane’s departure from her homeland, which becomes a reminder of her cultural identity in association with her grandmother. Yet, when she is confronted with her grandmother for rejecting her Iranian identity, their conversation is in the shadows. It indicates that as much as Marjane can attempt to alter her identity to adapt better abroad, her past will remain in her shadow and its rejection is futile. Marjane’s gradual acceptance of her dual identity is what liberates her to follow the dreams of those who did not have the same opportunity as her: their dream of freedom in identity and expression. It is with such acceptance though, that she is faced with the cost of distance and loss. Satrapi’s reason for writing the novel, and further directing this film is her attempt to reconnect with such distance and preserve what she can of her Iranian identity. And much like millions of exiles or immigrants, her story resonates universally.

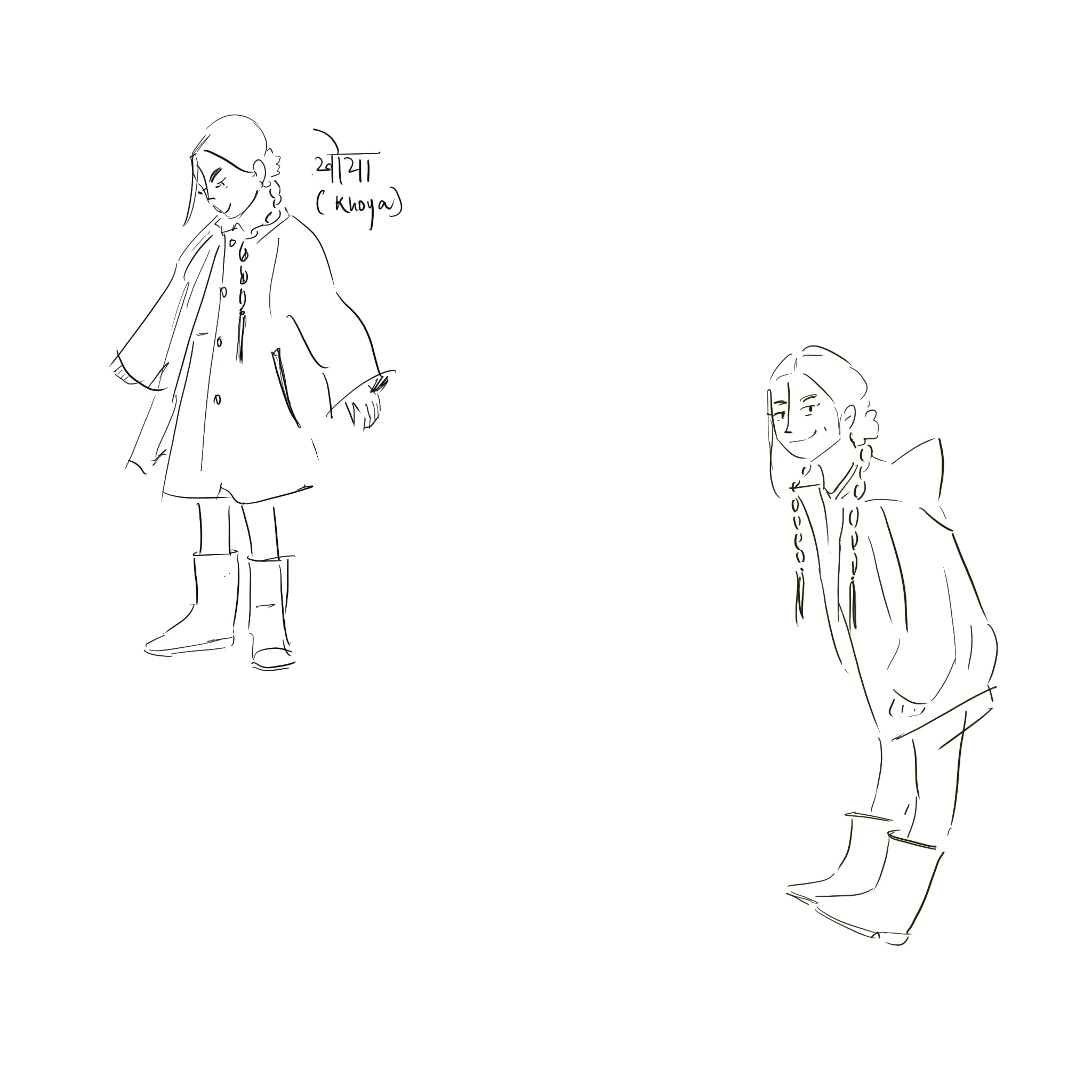

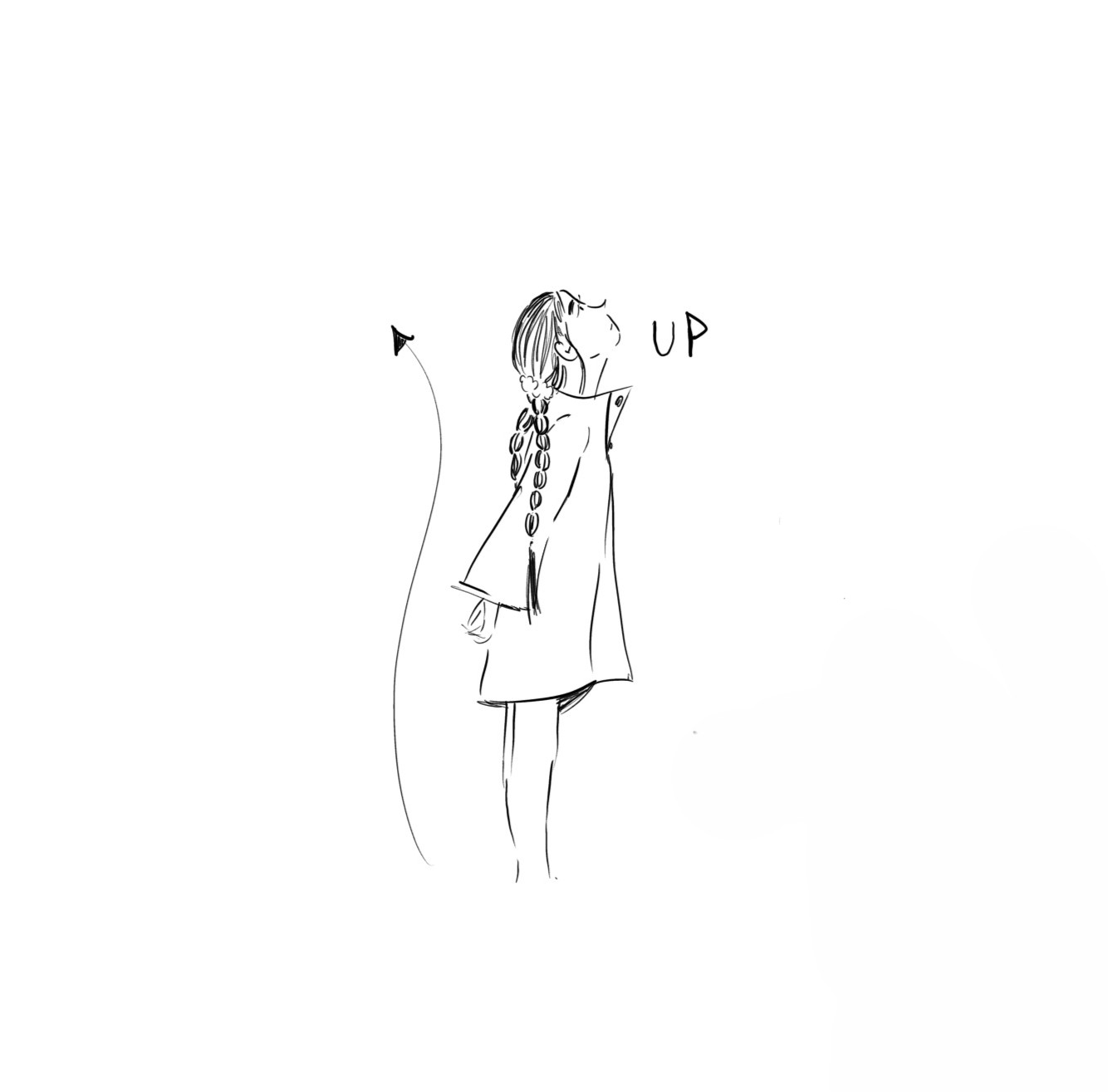

A short story that has been refined into a script from a 10th-grade essay prompt – Lost & Found. The notion that, to be found, one must have been lost in the first place, inspired an association that the two concepts are codependent. I then attempted to envision this through the personification of two characters lacking an ability, which they can find in the presence of one another. My creation of this short story into a film challenged me to push my boundaries as a writer dependent on words, to a writer that can incorporate this thought into a visual medium. I precisely imagine the script to follow an animation format, deeply inspired by the sketchy colour-dense illustrations of Holly Warburton.

1. EXT. FOREST – EVENING

The paws of a stray cat fidget against a hollow of red mud. Beneath it, a coin-shaped metal scrap appears, empty in the middle and rusted at its edges. Uninterested, the cat meanders on, to a scene that extends into the chaos of a forest, near a fence that overlooks a maintained garden. The margins of the fence are lined with shrubs of the same kind, each scattered with flowers of pink. It is an evening past a monsoon day, so the forest appears battered and orange, and the wet green of the shrubs offers contrasts.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Khoya, at the delicate age of 9, had already crafted herself a reputation. She was fickle, never at one place at a time, and perpetually worrisome.

The back of a little girl crouching through the opening of a fence. Her feet are bare, she wears a violet raincoat, and her long shiny braids sway to her movement. An end of her hair tangles with the fence, but she pays it little mind. Her attention is on a cat.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

She adored how white the moon looked against the canvas of a black night, the firey Palash flowers fallen on sparkly granite. And now, of course, the coat of a black cat as it ventured through the green meadow.

KHOYA’S MOTHER

Khoya!

Khoya does not flinch at the sound. Her eyes intently trace the movements of the cat. As she follows, her feet stumble beside a hollow of mud. The scene prolongs at the metal scrap within it until her feet exit the frame.

CUT TO:

2. INT/EXT. THE WINDOW OF AN INDEPENDENT HOUSE OVERLOOKING A GARDEN

Orange bougainvillaea adorn two ends of the window, and the panes are freshly cleaned. On the sill, there is a ceramic bowl filled with metal scraps dug out of soil.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

For Khoya’s mother, Tuesday was going just as predicted; it was lunchtime, and Khoya’s whereabouts were already unknown.

KHOYA’S MOTHER

Khoya Jaan!

KHOYA’S FATHER

I’d find it futile to call out her name.

The woman sighs in resignation. Her face is young, but her features are dulled. The grey under her eyes is confused between a lack of sleep and frequent coats of kajal. Unexpected to her appearance, she wears brightly coloured clothes.

2A. INT. BESIDE THE WINDOW OVERLOOKING THE INTERIOR OF THE HOUSE – KITCHEN

KHOYA’S FATHER

She’ll return. She always does.

A man sits at a table set for three. He beckons the woman to him. When she arrives, he begins to rub her back in consolation. The woman offers him a tense smile and finally sits down beside him. The scene remains at the table as time passes. The woman fidgets restlessly and only sips at her water. Her husband eats, kisses her forehead, and finally leaves. She falls asleep with her head on the table.

FADE TO:

3. INT. LIVING ROOM COUCH – LATE AFTERNOON

A little boy sits on a couch beside his mother. She holds on to him, caressing his hair while she silently cries. He sits composed, staring intently into space. His mother lets him go.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Milan spent his youth in exploitation. He was warm; his unwavering presence, reliable. After long days, his mother sang for him tears instead of lullabies so that his father could return home to a composed wife.

MILAN’S MOTHER

You’ll be okay, beta. Everything is okay.

MILAN

(hums)

Okay, mama.

(A pause)

MILAN’S MOTHER

My, did you get hungry? Papa will be home soon, he could make you something. Will you need a snack till then? The kitchen’s got –

MILAN

It’s alright, mama.

Milan’s mother dabs the corner of her eyes. She seems jittery and uncomfortable with her own state. She looks toward him to smile in gratitude, but his eyes remain fastened to the space beside her. Her face falls before she affectionately scratches his head instead.

MILAN’S MOTHER

Would you like to go outside? Stay close, though.

Unspeaking, Milan obliges. He walks toward the door, and his mother trails behind him with her hand on his back. He slips on a pair of sandals and exits. She sighs in embarrassment when the door clicks shut. Her demeanour is uptight, and the smile she forgets he did not see droops with her shoulders.

CUT TO:

4. EXT. THE GARDEN OF ANOTHER INDEPENDENT HOUSE – LAWN

At the far end of the garden, Milan settles on the lawn. He pulls up the ends of his trousers and rolls up his sleeves. His face lies under a patch of sunlight, but his eyes stay open.

(rustling sounds)

MILAN

(toward the sound)

Billy? Is it you?

Milan props up to a crouch and begins to feel around the grass beneath him. When he notices a presence, he reaches out to touch it. His hand lands on a turf of hair, which moves beneath him. His eyes widen, and he gasps.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

On Tuesday, for the first time in his life – Milan saw the silhouette of a little girl.

CUT TO:

5. EXT. THE GARDEN OF ANOTHER INDEPENDENT HOUSE – LAWN

Khoya follows the cat into a stranger’s garden. Unbothered, she looms over it when it eases its ministrations and rests on the grass. Just when she kneels to pet it, she feels herself get petted instead. At the same time that she gasps in surprise, there is a gasp behind her.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

On Tuesday, for the first time in her life – Khoya heard the whisper of a little boy.

[The following perspectives are alternated through audio-visual differences. * refers to Milan’s perspective, and ** to Khoya’s. * scenes are in black and white, and the visuals are hazy, but each sound is distinct. ** scenes are vibrant in colour, but the audio is muffled, almost mute, and the narrator’s voiceovers are in captions.]

MILAN

Oh boy, you’re not my Billy.

[**Both children separate and attempt to gauge the shock. Koya sees a fair boy with black hair in black clothes.]

NARRATOR (SUBTITLE)

Khoya appreciated the little boy’s attire, there was a lot of black, but his skin against it was white.

As Khoya examines the boy, his mouth moves, but the sounds are difficult to distinguish. When she tries to nod in acknowledgement, she notices his eyes are focused behind her. She turns to see what he may be looking at. It’s empty.

[*There is a vague outline of a girl. Everything in the scene switches to grayscale, as if from Milan’s point of view. The scene continues from the moment Koya turns her head away. The sounds are sharp, breathing, rustling, and ambient sounds are noticeable.]

MILAN

I apologise for having touched your hair, you see Billy…

(silence)

Khoya is still looking away.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Milan did not appreciate the little girl’s lack of response, perhaps she expected an introduction.

MILAN

Hello, my name is Milan.

The outlines of the figure almost disappear into the background. Milan squints and searches the space in front of him.

(footsteps retreating)

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Or perhaps he simply bored her.

KHOYA

We may have lost your cat.

Milan’s face lights up at the sound of her response. He looks grateful she did not get bored.

MILAN

Oh, don’t worry, Billy isn’t mine, but she’ll be back soon enough. Did you know cats have smell markers, so they use smells to mark their territory, it’s possible-

KHOYA

You and the cat have the same hair.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Milan concluded that this girl did not have manners. She never told him her name, why she was in his garden, and now, she interrupted him. Although he now had the newfound knowledge that Billy was probably a black cat. Not that he had a great sense of what black was like, but it was his favourite colour.

Milan’s expression contorts, to which Khoya lets out a loud and unabashed laugh. The outline of her figure moves along with the laughter but is still not clear. Milan makes a slightly disgusted expression at the sound but it begins to soften the longer he observes her.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Somehow, he hoped she never stopped laughing. And even though she was making fun of him, he felt his own traitorous laughter gurgle up at the pit of his belly.

Khoya’s giggles subside just as his begin.

KHOYA

I’m deaf. Maybe I talked in between or did not reply to you, but I’m deaf, don’t become offended.

The confession excites Milan.

MILAN

I don’t know the colour of black, but it’s my favourite!

[**The details of the scene clear up and transition to colour. Now the audio is muffled. Khoya tries to read his lips.]

Khoya watches him, confused. She mumbles to herself as if trying to read his lips, but is unsuccessful.

KHOYA

Yes, you wear lots of black.

Milan’s face drops before he tries again. He mouths the word ‘blind’ slowly, with the added gesture of his hands cupped over his eyes. Khoya smiles brightly when she understands.

NARRATOR (SUBTITLE)

Khoya realised that this could be why she did not mind it when he looked at her, maybe because she knew he would have nothing to see.

Milan smiles politely. But his front teeth jut out.

NARRATOR (SUBTITLE)

And although his smile was odd, Khoya thought it was the nicest one she had ever seen.

Milan extends his hand out to hers, which Khoya assumes is for a formal introduction. She reaches back to shake his hand.

KHOYA

The name’s Khoya. Khoya Jaan.

Instead, he flips her palm upward and begins to trace outlines on her skin.

MILAN

(The sounds begin to be heard clearly)

M…I…L…mil

A…N… un

Khoya’s eyes widen at how clear the sounds seem.

KHOYA

Milan!

MILAN

Yes! That is absolutely correct.

When he looks back up, Milan’s eyes land correctly on her face. Their eyes make contact.

KHOYA

I am Khoya.

Milan nods but does not repeat it. Khoya shifts uncomfortably with how intently he looks at her.

KHOYA

You know, you’re looking straight at me right now…

When he does not reply, Khoya becomes distracted and looks around for the cat. Her head faces away from him, but their hands remain in contact.

NARRATOR (SUBTITLE)

Khoya remembered the cat. She wondered where it could have gone before Milan had made her lose track.

MILAN

(in a soft voice)

I see you, Khoya.

Still looking away, Khoya scoffs.

[***The scene begins to merge, the audio and details become clearer, and the colours are more vibrant.]

KHOYA

But you’re blind.

Her eyes widen in realisation.

NARRATOR (V.O.) + (SUBTITLE)

Except Khoya had not yet read his lips.

When her head shoots back in his direction, Milan is already watching her.

MILAN

And you’re deaf – but you heard me, didn’t you?

The children smile at their mutual revelation.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

If touching her meant Milan could distinguish colour, he decided he would be willing to hold her hand forever.

KHOYA

Hey Milan.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

He liked that she enunciated his

name, just right.

He begins to nod, but she yanks their joined hands toward herself.

KHOYA

No! Speak it! I want to listen.

MILAN

(laughs)

Okay, Khoya. Will you move around? I think I could keep up with you.

Khoya’s shoulders bunch up in enthusiasm, and her gasp rises an octave higher than normal.

KHOYA

I hear you!

Milan is too much in awe of the shades and movements around her to find anything to say. His eyes try to chase everything. Khoya begins to slowly lead him away. They walk into the forest.

CUT TO:

6. EXT. FOREST – LATE EVENING

Hand in hand, the children wander into the forest. Khoya is in the lead, and Milan tries to soak everything around him. She intentionally crunches dry leaves, nudges stones and hums to herself. The evening rays trickle in through gaps in the rain trees.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

As the evening settles in, Milan wonders what the colour of her hair, clothes or shoes is named. And Khoya relishes in the sounds of

his gasps, footsteps and laughter.

6A. EXT. FENCE

Milan’s movements slow down as he catches a shine within the mud. Khoya stumbles to a stop in response. There is a metal scrap at his feet. It lies on a trail leading to a fence.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Khoya recalls the scrap to be one of the hundred her mother planted. It was the first time Khoya discovered escape, but seemed

to wander back home seeking out coins. Little could she comprehend why, at her feet, was the one thing her mother yearned for her to be; found.

KHOYA

I have arrived home.

Milan looks around, unable to gauge his surroundings. But he is calm, still smiling in awe.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Milan became aware that he could have finally been lost. And to his surprise, it did not worry him one bit.

KHOYA

Milan, will you teach me to sing a song?

Milan stiffens at the request. He is surprised but will not deny her. The surprise on his face moves into an expression of epiphany.

MILAN

Only if you teach me to dance to it.

From a distance, the children are seen crawling through the fence. Khoya effortlessly navigates through and then proceeds to hold both of Milan’s hands to guide him. They giggle when he slips. They run in the direction of her house.

FADE TO:

7. INT. KHOYA’S HOUSE – KITCHEN TABLE – LATE EVENING

Khoya’s mother still sits asleep at the kitchen table. A soft song wakes her.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Khoya’s mother almost hoped her daughter never left, maybe she was just missed and never heard them call out for her. Perhaps she got hungry now and will eat the meal set out for her. Surely, it could be reheated. But Khoya couldn’t sing, in fact, she had never heard a song well enough to replicate it.

7A. INT. CORRIDOR BY THE BACKDOOR

Khoya’s hands are around Milan’s neck, while he sings a song (Billy Joel’s Just the Way You Are). She tries to follow but falls behind by a couple of seconds. Simultaneously, she paces back and forth in simple steps. Milan trips here and there but almost keeps up with her. At the end of the corridor, Khoya’s mother leans beside the wall, smiling at the sight.

NARRATOR

At this moment, Khoya’s mother realised that for the first time in Khoya’s 9 magnificent years of childhood, she looked content in her own home.

FADE TO:

8. INT. KHOYA’S BEDROOM – NIGHT

Khoya is tucked into bed, with her father seated at the edge. The song Milan sang for her softly continues in the background.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Khoya, at the delicate age of 9, was embraced with relief in place of worry. Her mother fell asleep early that night and her father tucked her in. When her name fell off his tongue in farewell, she could imagine the sounds. Maybe his voice wasn’t sweet like Milan’s, but scratchy and low instead. She wasn’t restless under their watch now; she didn’t seek release. Because on Tuesday afternoon, for the first and last time, she found a boy named Milan.

9. INT. MILAN’S LIVING ROOM – NIGHT

Milan sits at the bottom of a staircase, with his head leaning against a wall. Across him, his parents dance to the same song from before.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

At night, when Milan found his way home, for the first time he was greeted with worry and warmth. His father made them his favourite meal, and his mother sang for them. As they danced, he imagined how his mother’s hips would sway, or the way his father’s eyes could look when he smiled. He finally felt relief, as if he could slip away and they wouldn’t need him at all. It was all because one day on a Tuesday afternoon, for the first and last time, Milan was lost with a girl named Khoya.

The song begins to fade, as the scene pans from the interior of the house, outside to the garden. On the grass of their lawn, a black cat scurries into the opening of a fence and escapes into the forest beyond.

FADE TO BLACK.