Intuitive Beauty in Adaptation

A curated catalogue exhibition on the adaptations of human perceived aesthetics as a collective evolutionary response to patterns in nature. The base idea was inspired by the following YouTube video, from which I speculated and researched its adaptation into art.

Intuitive beauty is the cognitive recognition of patterns within our environment that guarantees survival during our evolution (Biederman and Vessel, 2006; Mattson, 2014).

Certain complex coherent structures possessed by inanimate nature and life forms trigger an emotional response in humans, which we attempt to intellectually conceptualise as aesthetics (Hersey, 1999).

Neurophysiological studies clarify that the perception of an environment is determined by the tangible information it provides, and a comparison with internally stored biological/geometrical references (Kravitz, Peng, and Baker, 2011; Malcolm, Groen, and Baker, 2016).

These two neural mechanisms reveal the ability of the human brain to predict and interpret structural meaning based on innate and learned patterns derived from the natural environment (Nikos A. 234).

Natural patterns such as symmetries, fractals, meanders, tessellations, fractures, and many more create sensory biases exploited by the survival of natural selection to biological signals and further evoke human artistic innovation. This accounts for the observed convergence of structural forms in nature and decorative art (Enquist and Arak 169).

The exhibit Intuitive Beauty in Adaptation attempts to capture this contemplation on the origins of perceived beauty, through a rubric of selected natural patterns.

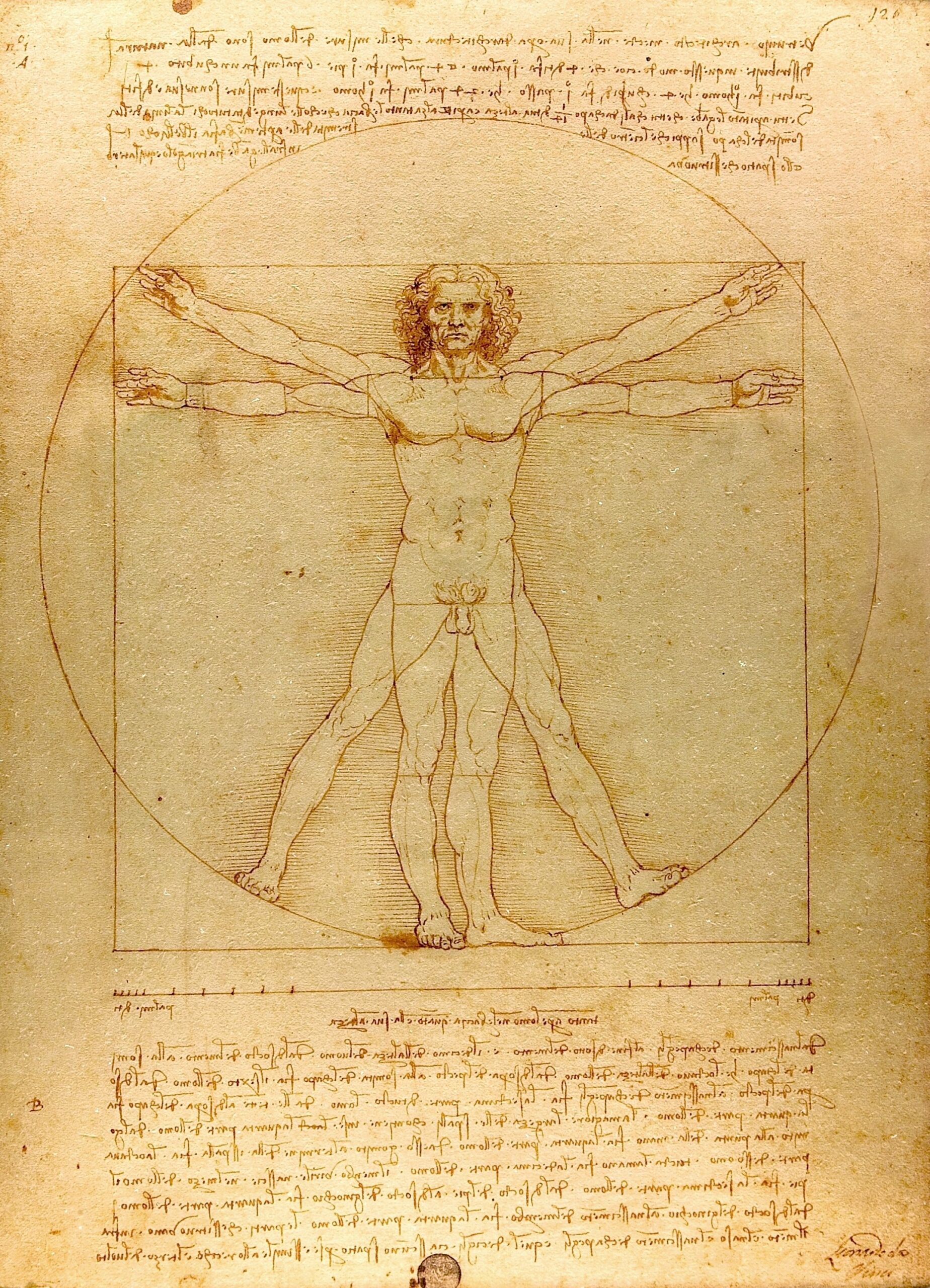

symmetry

Leonardo da Vinci

c. 1490

Pen, brown ink and watercolor over metalpoint on paper

34.4 cm × 24.5 cm (13.5 in × 9.6 in)

Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (1490), illustrates an ideal symmetry of the human form as both a standard of measurement and a driving force of civilization that transcends mere geometric proportions to embody a model of human performance (Strongman).

In correspondence, research indicates that preferences for symmetry have been observed to evolve to assess mate quality since deviations from symmetry suggest reduced fitness of certain species (Enquist and Arak 172).

The display assumes a connection between Vinci’s conception of ideal proportions and the intuitive sense of aesthetics that is evolutionarily derived from symmetrical patterns in nature. Vitruvian Man observes human anatomy as its natural reference to beauty, which is validated universally by its archetypal representation of the High Renaissance.

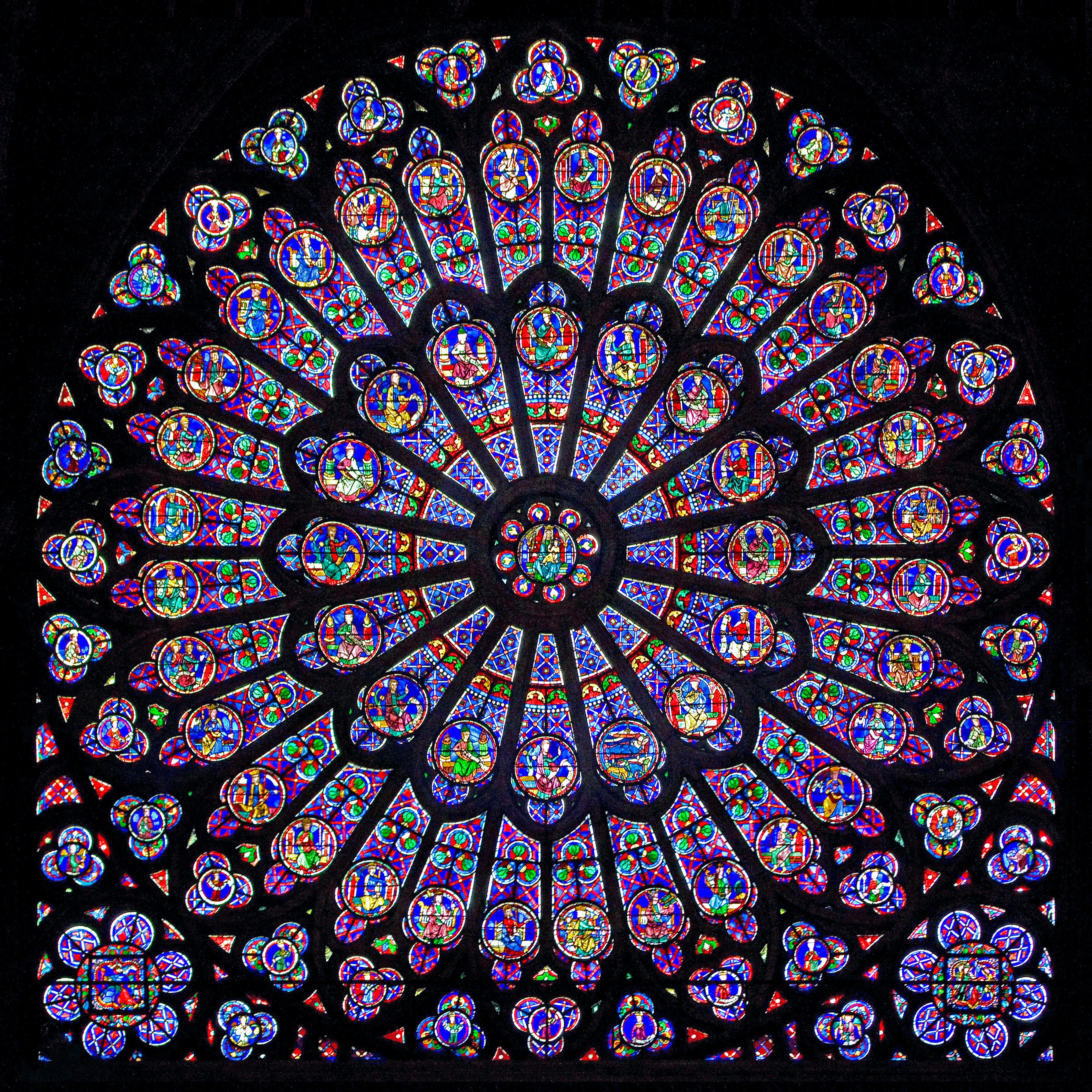

Krzysztof Mizera

August 2008

Photograph

2,209 × 2,209

Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris

An aesthetic feature of the rose window is its geometric interplay with natural light in Rayonnant Gothic Architecture. As per its name, the pattern resembles the overlapping arcs of rose petals, designed where mullions, or vertical bars, radiate from a central roundel, creating an intricate radially symmetrical pattern. These mullions often overlap, forming a complex arrangement of lights, each terminating in a pointed arch and frequently adorned with quatrefoils and other decorative shapes.

Floral symmetry has been an indicator of abundant nectar and a facilitator of cross-pollination. Research contemplates whether such indicators have an evolutionary appeal to humans because they suggest land and ecosystem fertility (Huss et al.).

fractals

Fractals are patterns that recur at various levels of a spatial scale. The continuity in fractal detail is pervasive throughout natural systems across different scales of observation. For example, in the branching structures of rivers, contours of landscapes, shorelines of continents, flow patterns of clouds, and so on (Friedenberg et al. 100).

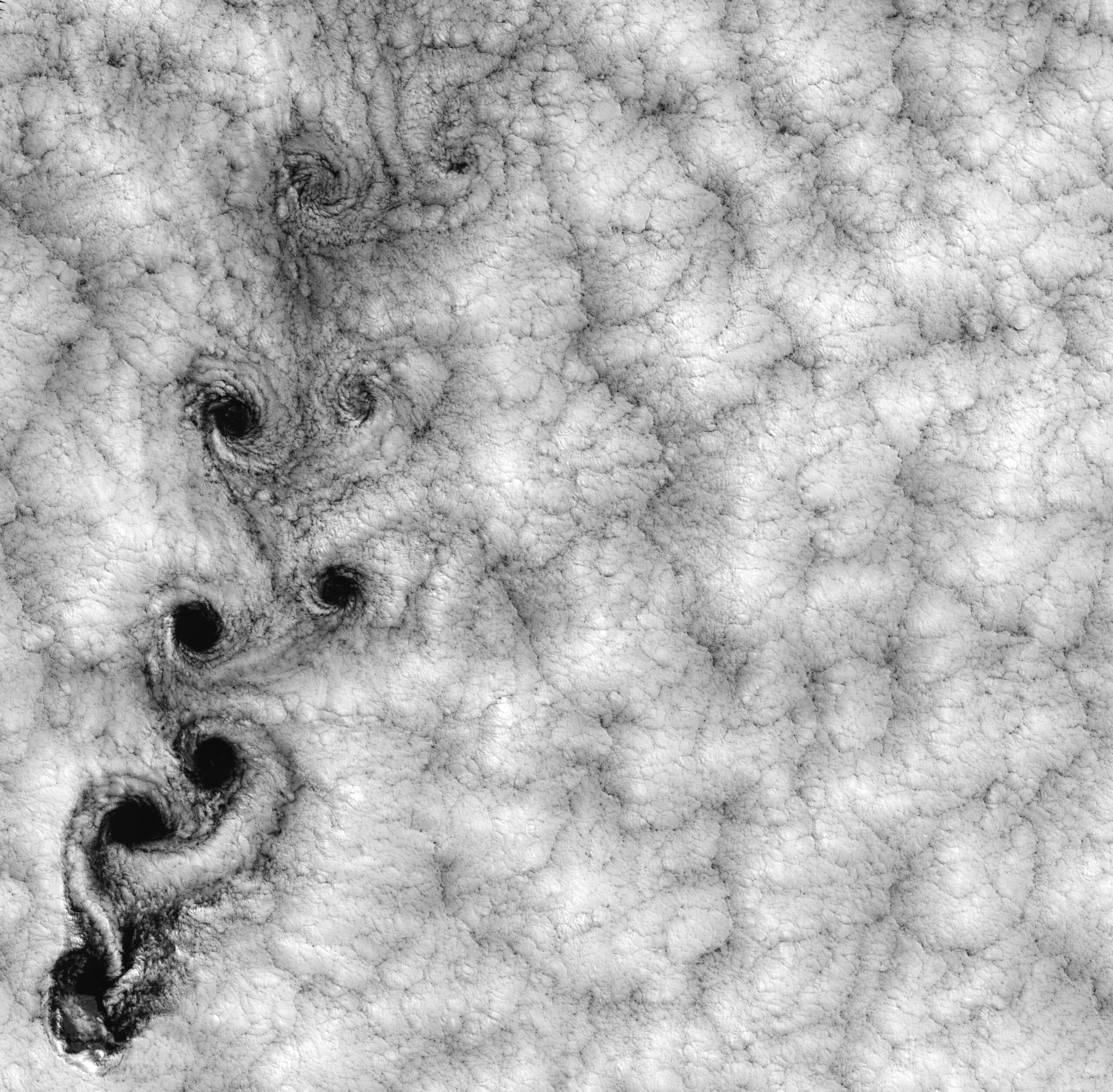

Image and caption courtesy Bob Cahalan, NASA GSFC

Published May 30, 2000

Satellite image

4664 x 4574

Chilean Coast Range, Mountain range in Chile

Captured on September 15, 1999, the Landsat 7 satellite image presents a distinct pattern of clouds known as a “von Karman vortex street” (or fractals) off the coast of Chile near the Juan Fernandez Islands.

This phenomenon has advanced human comprehension of laminar and turbulent fluid flow, which has significant implications in the field of meteorology (Cahalan). The marvel of its aesthetic and scientific value can be dated back to a survival response hardwired to predict or recognise weather conditions. Such survival indicators activate the reward centre in the human brain causing us to derive pleasure from fractal pattern recognition (Kurzgesagt).

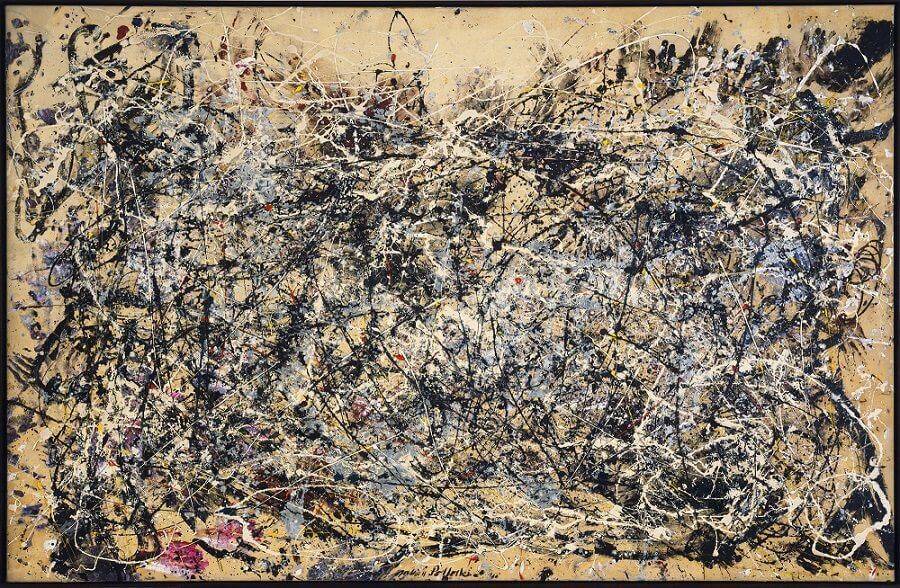

Jackson Pollock

1950

Oil and enamel paint on canvas

8′ 10″ x 17′ 5 5/8″ (269.5 x 530.8 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

One: Number 31, 1950 by Jackson Pollock employs a radical drip technique vital to his contribution to Abstract Expressionism. The dynamic gesture of this method strikingly resembles fractal patterns, which is analysed by mathematician, Richard Taylor in terms of its aesthetic value. The findings suggest that pleasure or stress reduction is the physiological resonance to fluent visual processing such as fractal imagery (Williams).

meanders

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

5 March 1753

Etching print and engraving

3,726 × 2,869

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

5 March 1753

Etching print and engraving

3,754 × 2,845

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Meanders are sinuous bends in rivers or other channels, which form as a fluid, most often water, flows around bends. Its resemblance in art has been conceptualised by William Hogarth in his book, ‘The Analysis of Beauty’. The Serpentine Line, or Line of Beauty, takes the form of an S-shaped curve, evoking movement and liveliness, one which ‘leads the eye in a pleasing manner along the continuity of its variety’.

Hogarth conjures six principles under his Analysis of Beauty, two of which are implications of the effect a meander or serpentine line has on the human aesthetic sense. The first, “variety” is claimed by Hogarth to be the source of beauty. This is a conditional factor, in which it requires relief from varietal experience, and hence must be a “composed variety.” This denotes his third principle, “composed variety”, a temperament of simplicity which enhance the pleasure of variety.

As observed from The Analysis of Beauty, Plate 1 and Plate 2, Hogarth’s breakdown of the applications of the meander, can be considered equally a natural phenomenon as it is a keen observation of artistic creation. It borrows from the composed variety of a meandering river, paving dynamic environments in support of diverse ecosystems. Its intentional sinuous course shapes a delicate balance in the habitats it can forge.

Ildiko Kovacs

1999

Oil on plywood

3,754 × 2,845

Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia

Ildiko Kovacs’ Serpentine, 1999, proposes a dialogue between the Western form of abstract expressionism and inspiration from indigenous Australian tradition, both of which seek confirmation in the natural world. The latter yields examples from aboriginal folklore, where the serpentine body resembles river pathways suggesting the presence of water.

Serpents have since been given importance as vessels of life, recognisably because of their meandering shape (Skidmore 67).

tessellations

A tessellation is the composition of well-balanced planes, shapes and geometry. It is determined by its inherent need for a space to appear closed within the structural formation. Preferences for tessellations in aesthetics imply sensory habituation to comprehend external stimuli as a whole rather than their respective parts (Parkar).

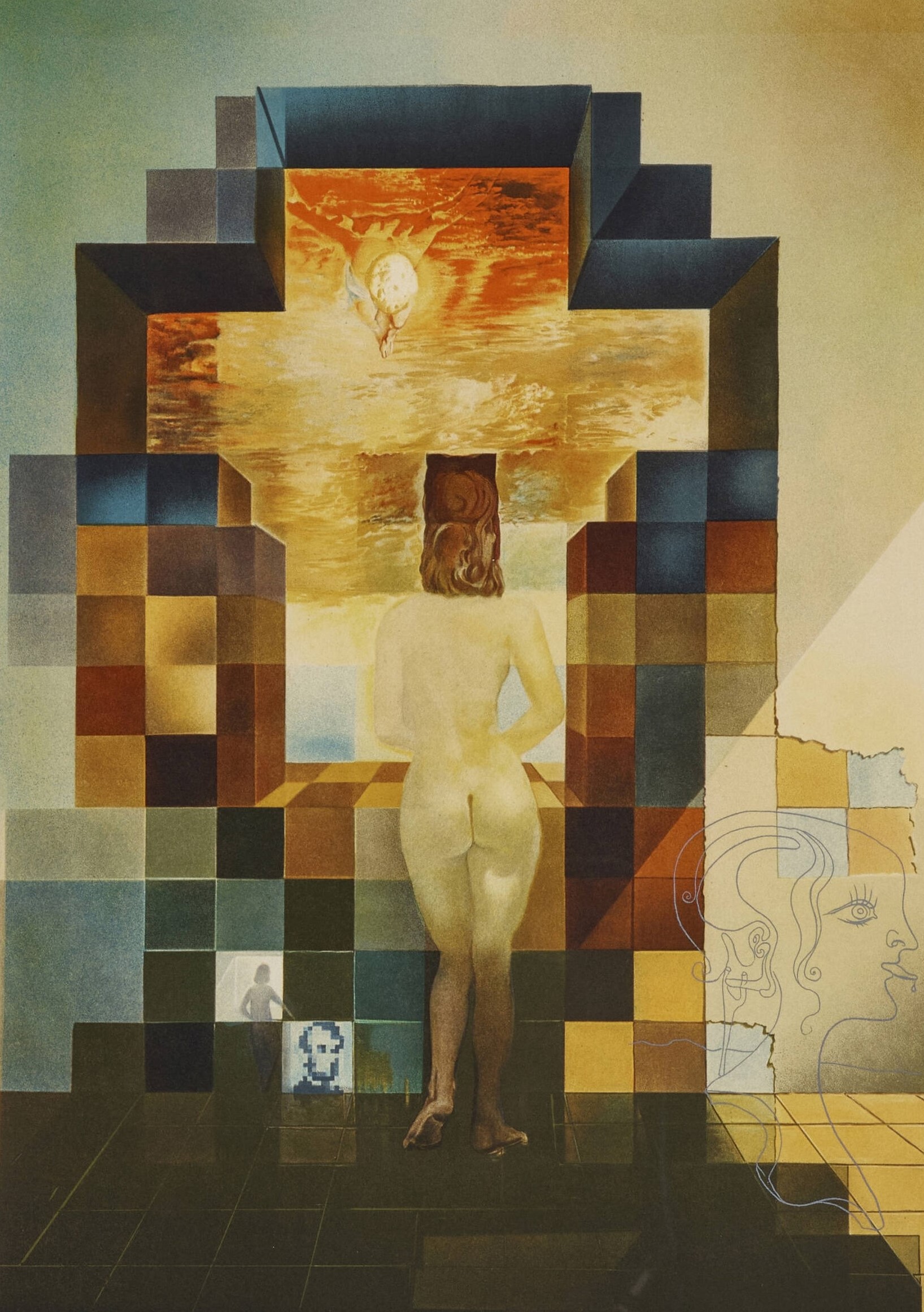

Salvador Dalí

1977

Photolith with original etched remarque and embossing

24 5/16 × 17 1/4 in | 61.8 × 43.8 cm

Dalí Theatre and Museum, Figueres, Spain

Salvador Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida, United States

Lincoln in Dalivision, layers multiple optical scales to create two paintings in one, awakening Dalí’s fascination with paranoia. The tessellations or pixel-type formation skilfully toy with subconscious familiarity and the capacity to perceive two images simultaneously.

Similar to how pattern recognition has evolutionarily suggested adaptability and comprehension of new environments, the immediate recognition of Lincon before Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea validates predictability in human perception patterns.

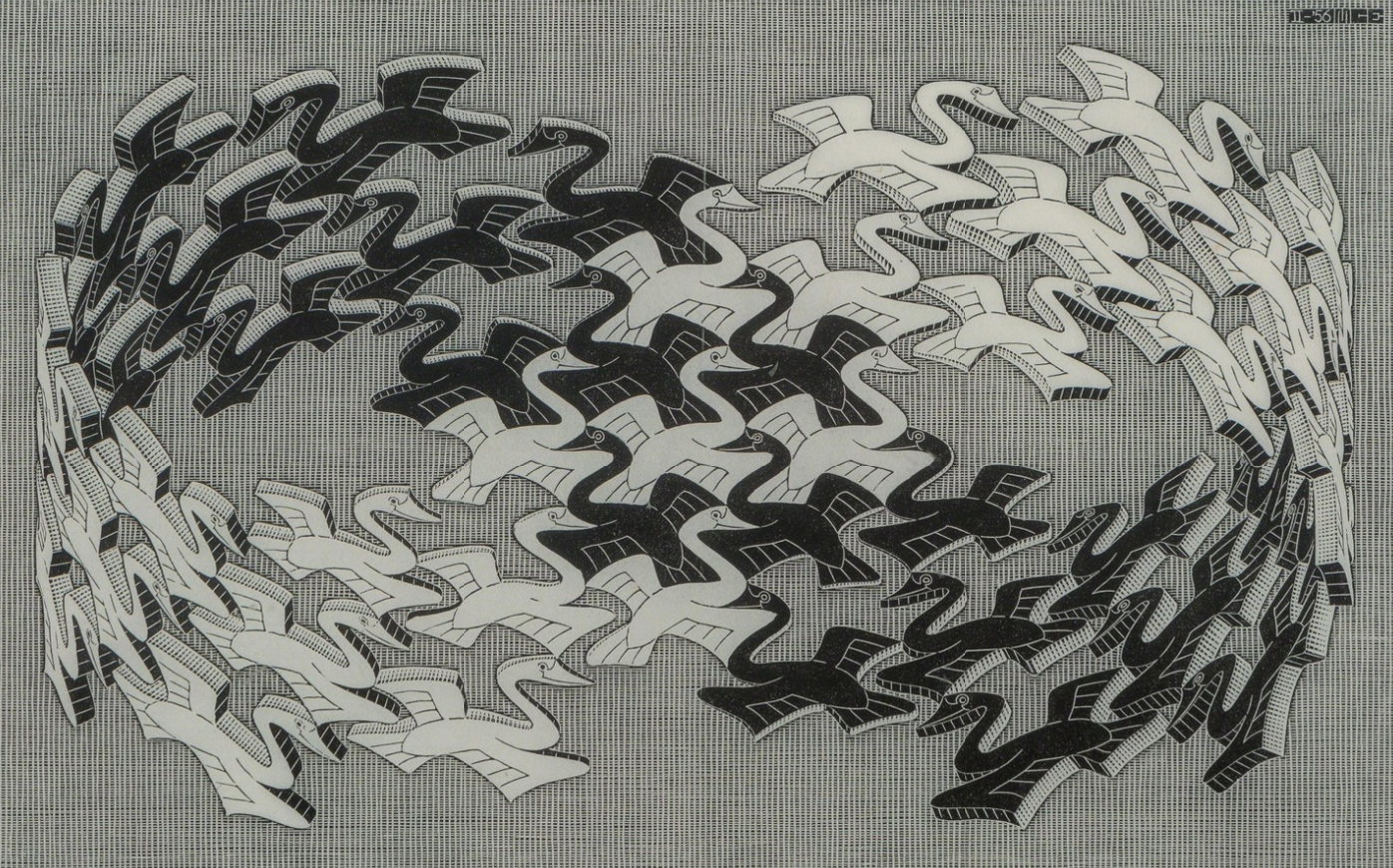

Swans (1956), exemplifies Esher’s more intricate tessellation work through its demonstration of glide reflexion. The technique precisely manipulates rotation and reflection within positive and negative space offered by tessellation to capture transformation through planes (Bennett 19).

Escher aligns the formation of swans such that they follow an infinite loop, a recurring symbol prevalent in his work.

The sense of eternity and the use of animal motifs propose a cycle of renewal and life. To couple patterns of tessellation with motifs from nature may not have been deliberate on behalf of Escher, but undeniably align with the impact such a pattern has on cognitive pleasure and aesthetic perception.

M.C. Escher

1956

Wood engraving on Japanese paper

30.48 × 40.01 cm (12 × 15 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art – Washington, DC

fractures

Fractures, or cracks are linear openings that form in materials to relieve stress. They can act as hydraulic conductors, providing pathways for fluid flow or barriers that prevent flow across them. Many petroleum, gas, geothermal, and water supply reservoirs form in fractured rocks.

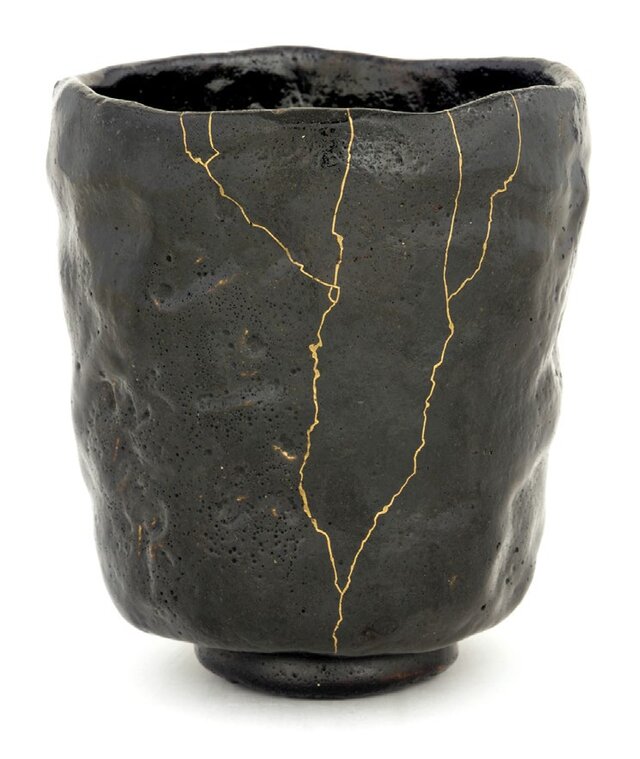

Unknown Raku ware workshop (Dosai, Dosai or Doraku)

Edo period, nineteenth century

Raku-type clay with Black Raku glaze; gold lacquer repairs

13.4 × 12.0 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

The Kintsugi Tea Bowl is an example of the renowned Japanese repair craft. It is a transformative process that uses urushi lacquer and gold or silver as a medium to mend cracks commonly in ceramics. Kintsugi attempts to demonstrate the unity of dual perceptions in catastrophe and amelioration. Contextualising the art form has drawn theories regarding its geological and cultural origins in Japan.

Such conditions posit that the Japanese experience of earthquakes, particularly within their geo-ecologies, has likely influenced the adoption of this craft technique (Keulemans 16).

Cracks are conceptualised as affects that involve the transmission of forces that traverse through material entities, extending into sensations. These sensations establish perceptive connections between individuals and their interactions with objects or their environment. The resonance of cracks as a natural pattern is an integral form of what composes beauty in the art form, which could be the sentimental derivative of cracks that result from earthquakes (Keulemans 22).

Yeesookyung

2013

Ceramic shards, epoxy, gold leaf

61½ by 36 by 27½ inches

Locks Gallery, Philadelphia

Adopting the same technique of Kintsugi yet in a transformative manner is the installation, Translated Vase by Yeesookyung.

The composition attempts to mend rejected shards of ceramics by Korean potters in their pursuit of the perfect vase.

The high beauty standards prevalent in Korean and East Asian culture are associated with this need to achieve standardised perfection, which the artist reimagines through her work.

She captures beauty from the neglected shards, similarly employing the techniques of Kintsugi. The adaptation retains the pride of fractures within the ceramics through its gold-mended junctures (Gómez 7).

conclusion

An inquisitive observation I came across during my curation of Intuitive Beauty in Adaptation, was how it intersects with subjective or learned perception of beauty. While there are convincing arguments in favour of our intuitive preferences for art that resemble natural patterns, where does that come into place when we don’t limit ourselves to ‘art’? Consider the evolutionary conditioning that has shaped conventional standards of beauty today. What we consider ugly in fact, has greater resemblances to natural patterns. We seem to have lost the ability to introspect what we appreciate from external beauty.

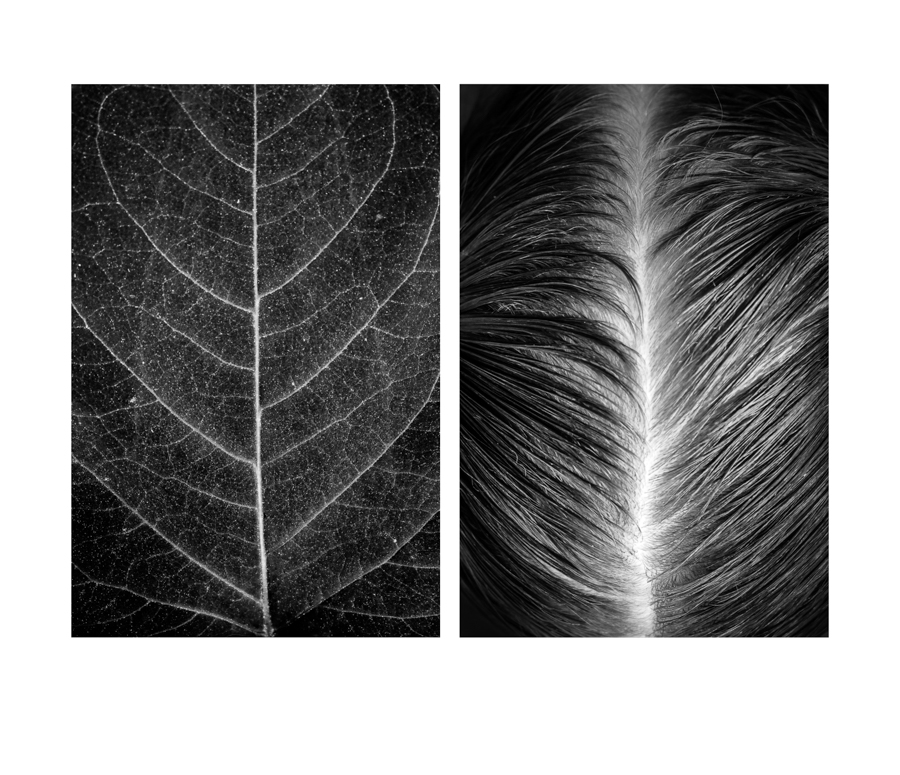

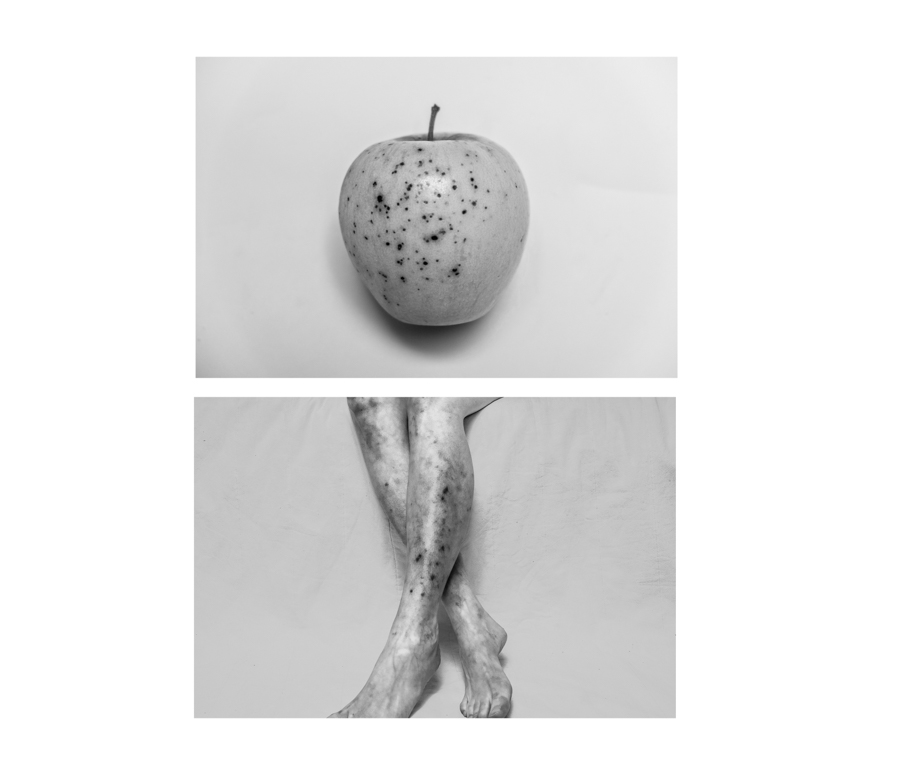

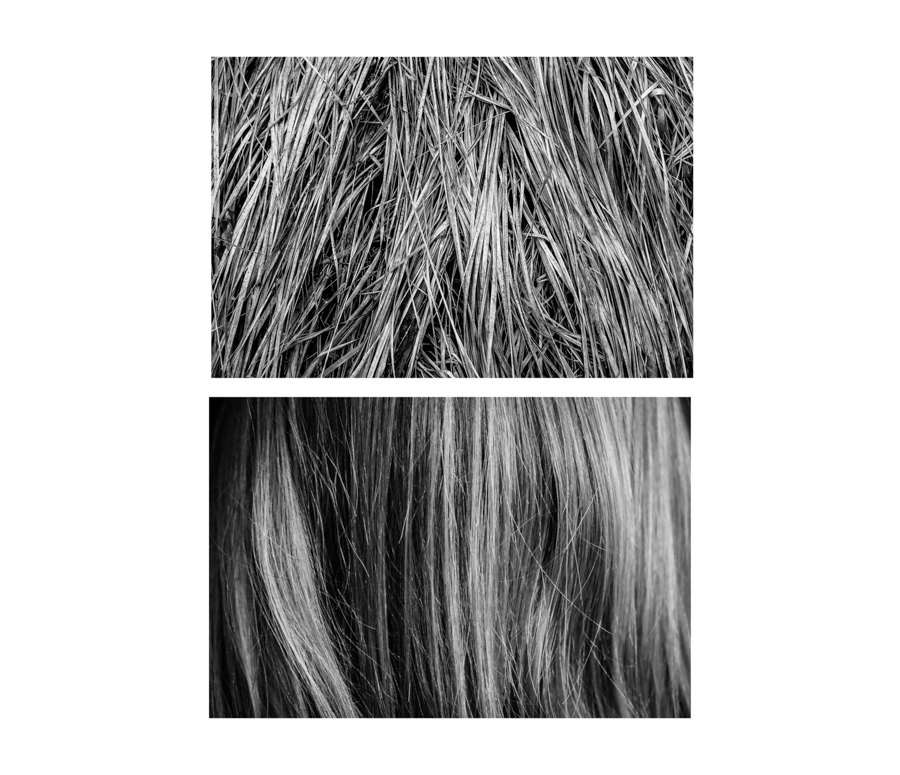

My final selection is a series of diptychs photographed by Alicja Brodowicz. She retraces the interrelation of the human body and nature, blurring the lines between perfection and abnormality, suggesting a perfection of both. Brodowicz quotes, “Estrangement from nature has led to the abuse of the environment and the body. Only through a reconnection with nature can we rediscover self-love and make the imperfect body perfect once more.”

Alicja Brodowicz

2018

Photograph